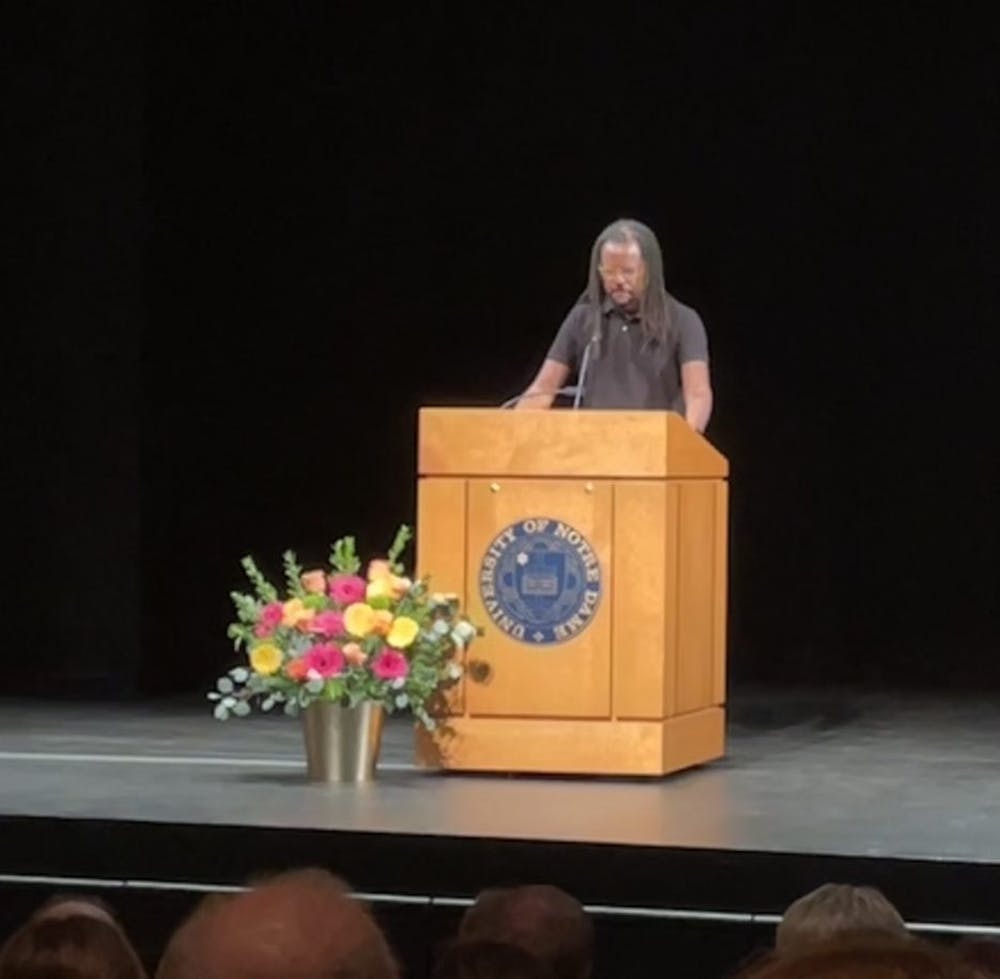

The floor of Patricia George Decio Theatre in the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center was brimming with anticipation on Wednesday for “A Conversation with Colson Whitehead.” The two-time Pulitzer Prize winner for fiction was this year’s Rev. Bernie Clark C.S.C. Lecturer, a discussion established by the Center for Social Concerns in 2009 for the purpose of illuminating those who promote justice, human dignity and the common good.

The lecture began with a welcome from Suzanne Shanahan, Executive Director for the Center for Social Concerns, and John McGreevy, Provost of the University of Notre Dame.

McGreevy began his address by describing Whitehead as “one of the contemporary world’s most distinguished writers.”

“He moves seamlessly between genres, from speculative fiction to coming-of-age satires, to magical realism. He’s written about elevator inspectors, zombie hunters, professional poker players, and adolescents” said McGreevy. “The better question is, what hasn’t he written?”

Whitehead took to the stage after and quickly got the crowd laughing with stories of his childhood in Manhattan. He joked that he “would have preferred to have been a sickly child” as an excuse for his journey into creative writing rather than “just not wanting to go outside.”

He traced his roots in writing to a series of “five-page epics” he had written to apply for a creative writing class which ultimately rejected him. Then on to a short stint in journalism for The Village Voice in New York, granting him enough confidence to make his first attempt at novel writing, which again resulted in a string of rejections from publishing houses.

The writer compared his early struggles to the song “MacArthur Park” by Richard Harris, in which the singer agonizes over a cake left out in the rain.

“Houghton Mifflin publishing group, why did you leave my cake out in the rain?” Whitehead joked

On trying to catch the attention of not only publishers but readers as well, Whitehead said, “You’re not even a gnat trying to catch the attention of an elephant; you’re a microbe in the butt of that gnat.”

Whitehead also stressed that he “didn’t want to scare any aspiring writers in the room”, and that his early rejections allowed him to write with less trepidation and accept increasingly unorthodox concepts for his novels.

He went on to cite several story ideas which had originated from unlikely sources.

His first book, “The Intuitionist,” was inspired by watching Dateline NBC, Whitehead revealed.

The show had a special on the hidden dangers of escalators, involving testimony from an inspector.

“I thought it would be weird if an elevator inspector had to solve a criminal case," he said.

Whitehead said his zombie novel, “Zone One,” came from a dream. He described how a series of nightmares he first noted after watching “The Evil Dead” with his parents propelled him to write the story, now a New York Times Bestseller, decades later.

Whitehead next discussed his 2011 historical fiction titled “The Underground Railroad,” in which an escaping slave utilizes a chain of literal underground train stations on her journey to freedom. He admitted that he held on to the idea for a long time before committing it to writing.

“It was such a good idea, that I knew if I tried it back then I would have screwed it up,” Whitehead professed.

The novel earned Whitehead his first Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

“Periodically the scary idea, the one you have been avoiding, is the one you should be doing,” Whitehead said.

The last story Whitehead touched on was “The Nickel Boys,” his second Pulitzer Prize winning novel. The story is based on the Dozier School, a reform institution in Florida which was known for enacting highly abusive practices on its students.

Whitehead reaffirmed that he paid close attention to how he could best enunciate this idea to his audience and do the story justice.

He said, “The writer’s job is to find the right words so other people can see the world the same way you do.”