I recently went to a comedy show performed in Washington Hall with rakish jokes and sardonic impersonations. In 1924, other white, male students went to the same building to watch a similar comedy show. I could lift a review from the April 1924 edition of Scholastic and apply it to the show I saw: “Nothing but foolishness from beginning to end, of course; but such hilarious, idiotic, downright funny foolishness as it was!”

What was the difference between these shows performed 100 years apart? Notre Dame students used to put on blackface minstrel shows.

Minstrelsy has been an influential force on American culture. Popularized by Thomas “Daddy” Rice, inventor of the Jim Crow character, minstrelsy took off in the first half of the 1800s and reached its peak between 1850 and 1870. After 1870, minstrel shows moved from professional theatres to amateur performances. Around the same time, the existence of blackface at Notre Dame is first recorded.

Besides the presiding interlocutor, it was standard for the (white) performers to artificially darken their faces, portraying African Americans with exaggerated features. Later, African Americans were made to play caricatures of themselves while in blackface. Minstrel shows and blackface’s foothold in American culture persisted into film and cartoon. One can look up clips of Judy Garland as a minstrel performer in ”Babes on Broadway” or Bugs Bunny in blackface in ”Merrie Melodies.”

As Ava Rawson writes, “the history of blackface is as American as cherry pie but twice as bad for the heart.” Blackface is a degrading caricature of Black people that spawned from white fear of equality. Its widespread popularity demonstrated a cultural belief of Black inferiority that justified control during slavery and separation after slavery. For some, typically in the North, this was the only perception of African Americans available. Founded in 1842, the University of Notre Dame has naturally reflected American culture. Notre Dame, like the country, has a forgotten legacy of blackface and minstrel performance.

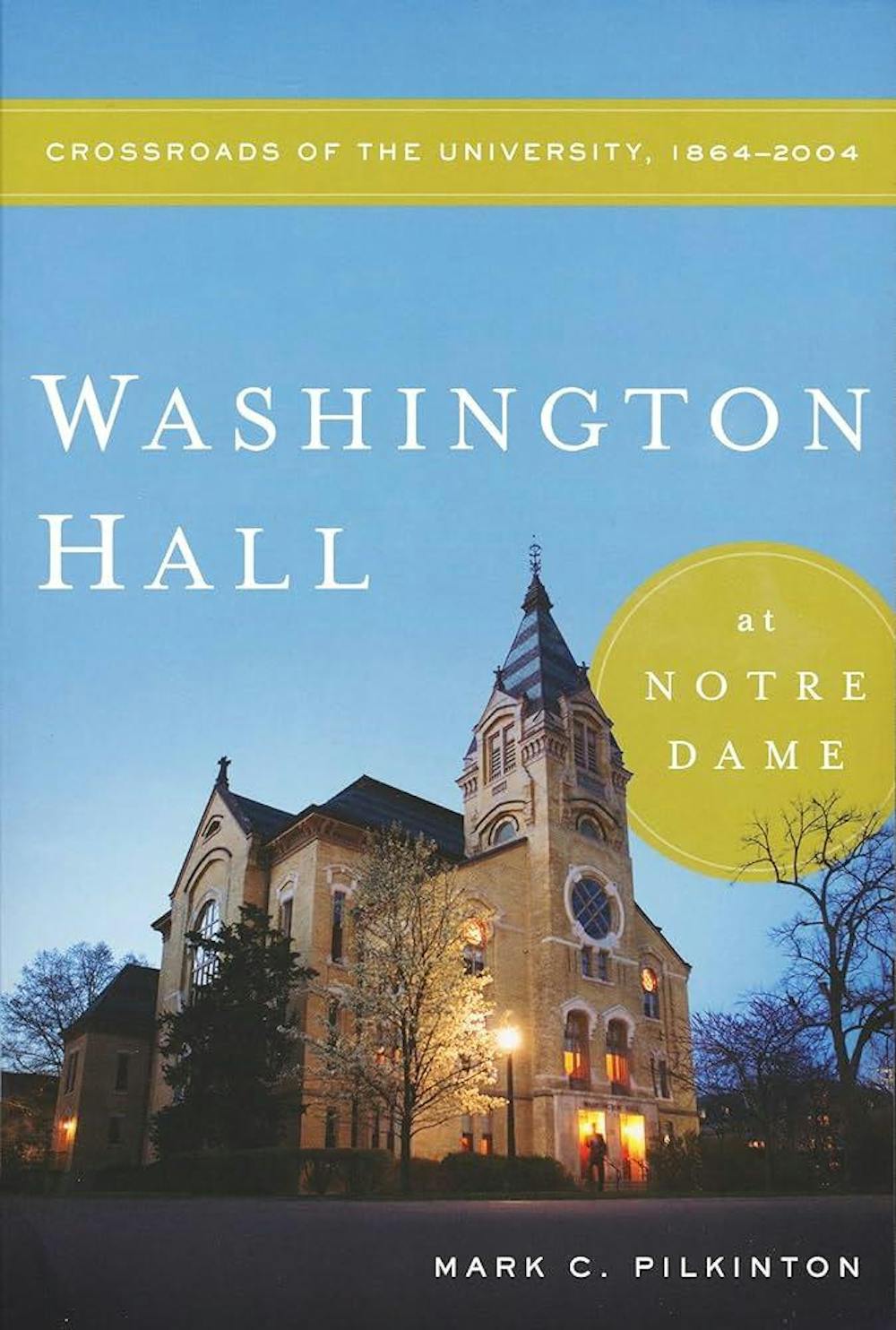

The first recorded instance of blackface on campus was in 1870. A performance of ”The Upstart,” a rendition of Molière’s ”Le Bourgeois gentilhomme,” saw the addition of what one viewer describes as two “’cullud pussuns ...’ personified ugliness ... hideous as sin.” They were said to have been greeted with “merry shouts.” These Black characters were especially out of place in this 1600s play. In fact, they had replaced female roles. As professor emeritus Mark Pilkinton has noted in his book ”Washington Hall at Notre Dame,” this instance evidences “the notion that it was more acceptable for a young white man at Notre Dame to portray an ethnic male than it was to portray a white woman” since the early University either did not include female theatrical roles or changed them to male characters of color. This can be seen on other occasions, like in 1898 when, in a production of ”A Night Off,” the professor’s servant (a woman named Susan) was changed to “Sambo, a colored boy.” The role was clearly a mockery. Sambo was a pejorative term for an African American. It was written in Scholastic that the performer’s “dialect was faultless” and “well deserved the applause that was so freely given him.”

The first solid record of a full-blown minstrel show (not just blackface) at Notre Dame comes from an advertisement in Scholastic in 1907. The Corby Hall Glee Club was preparing to put on a “black-face minstrel” which was called “something new at Notre Dame” that would “be looked forward to with much interest and satisfaction.” It was not long before things like “May Day Minstrel” shows were a reality. In the 1914 yearbook, one photograph shows twenty-six of thirty-two performers in blackface onstage.

Knute Rockne was said to have performed in blackface but was incapable of holding his dialect. In the mid-1920s, notable figures like Jim Crowley, one of the Four Horsemen of Notre Dame, and Clarence Manion, later dean of the law school, performed in blackface. In 1928, Father John Devers’s return from Pennsylvania was met with a blackface comedy show along with academic talks and orchestral music in an event put on by the East-Penn Club and Badin Hall, where he was rector. Such performances were not considered edgy undergraduate provocations. They were commonplace.

As the 1930s came to a close, minstrelsy began to lose its appeal at Notre Dame. The Monogram Club replaced its racist minstrels with sexist, parodic drag routines according to Pilkinton’s book. In the 1940s, blackface was no longer a performance advertised for the whole campus, it was reserved for things like the 1948 Rebels Club’s Mardi Gras celebration ... but that was a club celebrating the Confederate States of America. Still, as late as fall in 1957, the band’s halftime show theme for the Iowa game was ”Minstrel Show.” The show almost certainly eschewed blackface. A Scholastic article speaks of ”featuring songs of the minstrel show days in the South” that seem to have concluded.

Why point all of this out? A considerable reason we learn history at all is to avoid replicating the unsavory parts of the past. The same applies here. We must recognize that sordid stereotypes and jokes echo a racist past. It is not controversial to condemn louche actions that lead us away from social progress. It takes vigilance to avoid slippery slopes.

Vincent Micheli

Class of 2027

Jan. 16