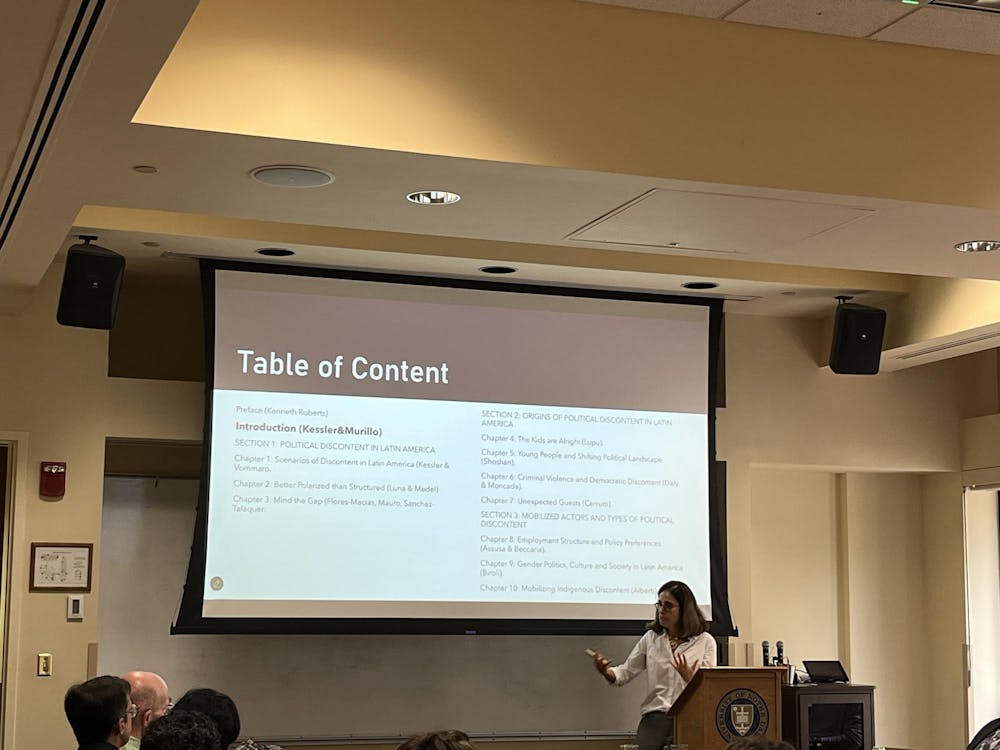

Tuesday afternoon, Maria Victoria Murillo, a professor of political science and international affairs at Columbia University, presented on her upcoming book in the Hesburgh Center. Her work addresses questions as to why many Latin Americans are increasingly disillusioned with democracy, despite social progress. It is co-edited with Gabriel Kessler, an Argentinian sociologist and professor.

In her book, Murillo explores the paradox of widespread political discontent amid improvements in poverty reduction, education and expanded rights. She discussed this paradox in her lecture, explaining that rising expectations and broken promises have generated social frustration and political reactions.

Murillo, who holds a PhD from Harvard University, explained the two ways this can be manifested.

“One expression that we call vertical discontent, that is more systemic, people are unhappy with all political elites, this is shown in electoral representation, in elections,” Murillo said.

Murillo claimed that Guatemala’s 2019 presidential election is evidence of this vertical discontent, where the two most-voted candidates received 25% of the vote, and the eventual winner in the second round of the election, 14% of the vote. She suggested the election shows that people are not happy with any of their options.

Murillo also described horizontal discontent, which is “when the people dislike the government, but also dislike the coalition that supports the government.” She added that in most Latin American countries, polarization occurs around singular focal points rather than political parties.

Murillo further described protests as a way that Latin Americans have expressed their discontent.

“People have a clear way of organizing their discontent. And in terms of protest, although I have to say we saw less protest, but we do see protest here,” she said.

This evidence of discontent sparks questions about the origins of dissatisfaction, which Murillo attributes to economic and political instability.

Murillo noted that throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the region suffered, and during the 2000s, the commodity boom, especially in South America, had a dramatic effect in terms of growth, decline of poverty and inequality. After 2014, there was not a crisis, but rather a slowdown in growth, therefore, changing the expectations of people.

“[The slowdown] generates this sense of relative deprivation, that even though things were not necessarily going into a crisis, you see that the trajectory was not there anymore. And that increasing over time brought people to blame the government, because we know Latin Americans tend to blame and reward the government for socioeconomic conditions, and that generates this longitudinal effect on political discomfort. They start to be much less tolerant of crime and corruption, and that’s what we associate with protests, with an incumbent vote, with increasing electoral volatility,” Murillo said.

Murillo thinks there will be an evolution, and while she cannot map what is happening in the current moment, she has made predictions about the future, which she will share in her book.

In the conclusion of her lecture, Murillo acknowledged the impact of social media and access to information to contribute to political discontent around the world. She shared that the chapters in her book highlight the impact of medium-term social gains associated with democratization and a continuous process produced by weak state capacity, such as public insecurity, which maps to within-country variation on political discontent and even political participation.

“The framework for understanding political discontent based on the historical experience of Latin America focused on feelings of relative deprivation as the positive trajectory of the boom decelerates even before the pandemic ... It’s not a reaction to a crisis but a continuous process and hasn’t yet produced a stable political equilibrium,” she said.