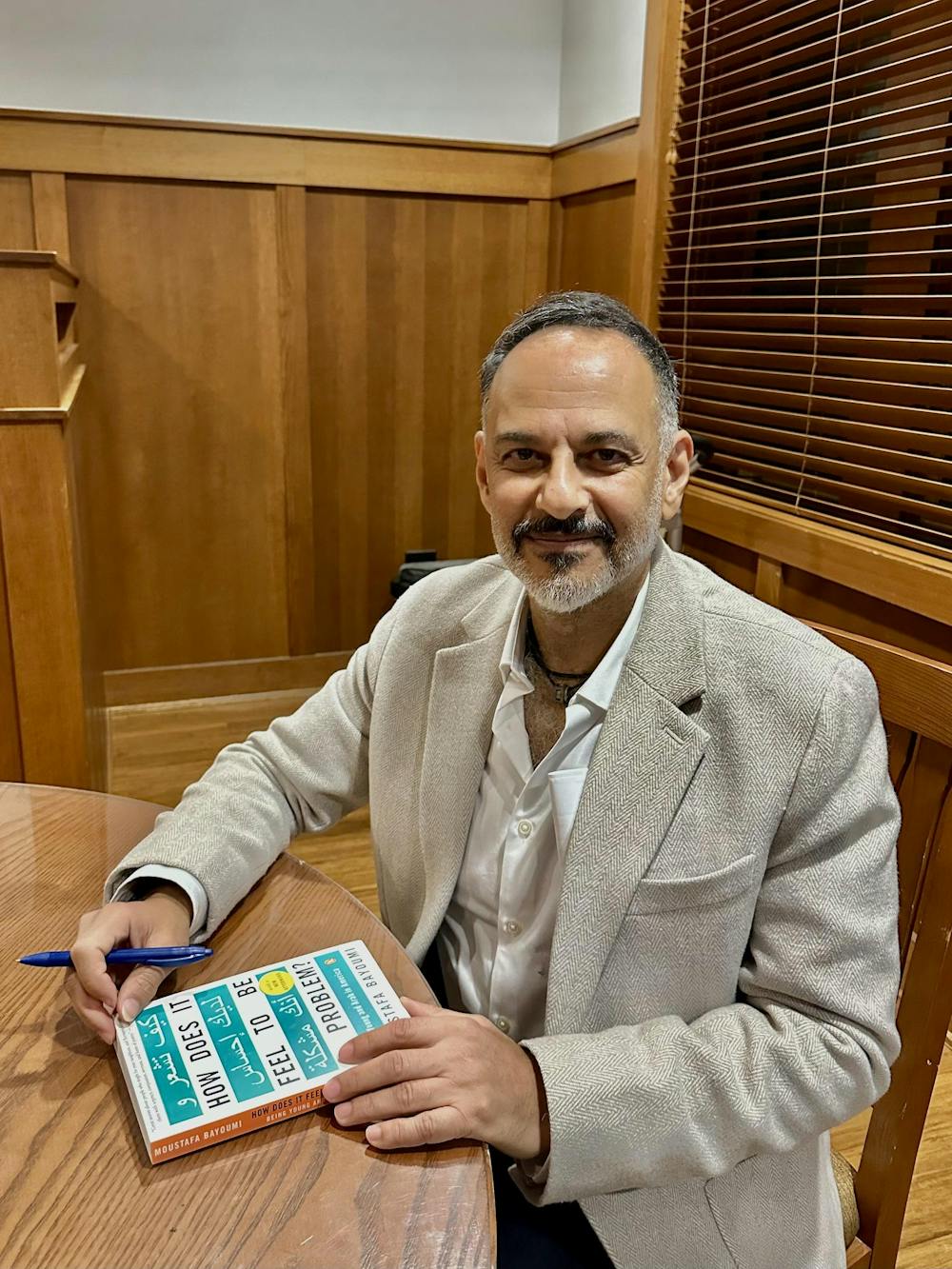

Moustafa Bayoumi, journalist, author and educator, spoke Thursday evening for the Literatures of Annihilation, Exile and Resistance research collective and lecture series. The series is dedicated to exploring contemporary literature that focus on exile, transnational migration and human rights violations. The dialogues bring together speakers from the United States, North Africa and Southeast and Southwest Asia.

In welcoming the author, Notre Dame professor of Islamic thought and Muslim societies Ebrahim Moosa described the significance of Bayoumi’s writing.

“There are moments, rare and difficult moments, when a writer does more than record events. He widens the moral aperture of a nation struggling to see itself. He invites us to stand at the threshold where clarity and compassion meet,” Moosa said.

Bayoumi’s book, “How Does It Feel to Be a Problem?: Being Young and Arab in America,” embodies “A question born out of the black experience forged at the furnace of American racial history,” Moosa said. “In choosing that title, Bayoumi performs a deliberate act of intellectual kinship, a gesture of solidarity that refuses to isolate Arab and Muslim immigrants from the long black struggle for belonging and dignity.”

The book focuses on the stories of seven young Arab Americans living in Brooklyn, New York, spotlighting distinct yet interrelated experiences of their lives post-9/11 Brooklyn. The book is structured as a feature magazine story, centering the distinct stories of each individual while keeping itself grounded.

Bayoumi begins his speech citing the Arabic language as a linguistic time bomb, “Pay close attention and you can hear it ticking second by second toward the imminent explosion of our society,” he said.

He explained how the post-9/11 era brought fears from Americans toward any Arabic speech, as the language was perceived as alien to the United States.

“If you think I’m being hyperbolic, can you name any other language that excites such extraordinary levels of fear and acrimony in the nation today?” He said.

He narrows in on the Arabic word “intifada” as an example of this linguistic fear. Bayoumi described how this word is commonly heard within the broader phrase “globalize the intifada” at rallies in defense of the Palestinian people. The word means shaking off or shaking off one’s oppression.

In a brief historical overview, he explained how the word was first commonly used in Iraq in 1952 to overthrow the British-installed monarchy in favor of a republic. In 1987, the uprisings of Palestinians in the occupied territories was labeled as the intifada, followed by the second intifada in 2000. Both of the uprisings consisted of mass protests and civil disobedience.

Both movements were largely nonviolent, but there were devastating impacts. The first intifada resulted in 200 Israelis and 1000 Palestinians being killed, and the second intifada resulted in the killing of 1000 Israelis and 4000 Palestinians.

Bayoumi explained how the word intifada has been consistently mischaracterized by mainstream discourses. Citing political scientist and professor Seth Canty, Bayoumi shared how “Calls to globalize the intifada are not calls for genocide. They are calls for resistance, including armed resistance to decades-old Israeli military occupation widely considered illegal under international law,” he said.

In his own words, Bayoumi expressed how “My point is that the political classes who come with a clear anti-Palestinian political agenda and don’t speak Arabic should not get to define the meaning of the Arabic language for the rest of us.”

Situating the vilification of the Arabic language within the war on terror, Bayoumi cites multiple examples of the disturbing reality Arab Americans are faced within their daily lives.

In 2006, Raed Jarrar was not allowed to board his JetBlue flight because he was wearing a shirt which read “We Will Not Be Silent” in English and Arabic. The TSA agent demanded for him to cover the shirt, stating it is impermissible to wear an Arab shirt to an airport and equated the action to a person wearing a t-shirt at a bank stating I am a robber.

Two Palestinian men in 2015 were asked to step aside when boarding their flight after passengers heard them speaking Arabic. One of them was carrying a small white box containing baklawa, which he shared with the rest of the plane after both men were allowed back on the flight.

Khairuldeen Makhzoomi was removed from his flight in 2016 after another passenger heard him speaking Arabic on the phone. After being escorted off the plane, he was asked why he was speaking Arabic considering today’s political climate.

“It’s a cute story, but I do long for the day when I don’t have to share my sweets with the bigots to buy off their fear,” Bayoumi said.

He mentioned the war on terror has led to the deliberate toxic relationship Americans have with the Arabic language and its application of it.

“Such linguistic loathing, in other words, is not due simply to the ways that Americans are notoriously bad at learning languages or the almost uniquely American belief that the world of languages must bend to them, but is instead clearly related to the elaboration of the war on terror. This forever war against a noxious political tactic, has led to monster making of anything associated with America‘s new but now eternal enemy, Islam,” he said.

Moosa reflected on the moral integrity and urgency of Bayoumi’s writing in this current moment.

“Bayoumi reminds us that the struggle for Palestinian dignity, the struggle against Islamophobia, the struggle against antisemitism, the struggle for American belonging, these are not separate battles. They are interwoven threads in the fabric of a just society and they demand a moral vision capacious enough to hold complexity without collapsing it into contradiction,” he said.