On Jan. 27, the Nanovic Institute for European Studies hosted its annual Holocaust Remembrance Day lecture. The United Nations designated Jan. 27 as Holocaust Remembrance Day in 2005, which marked the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.

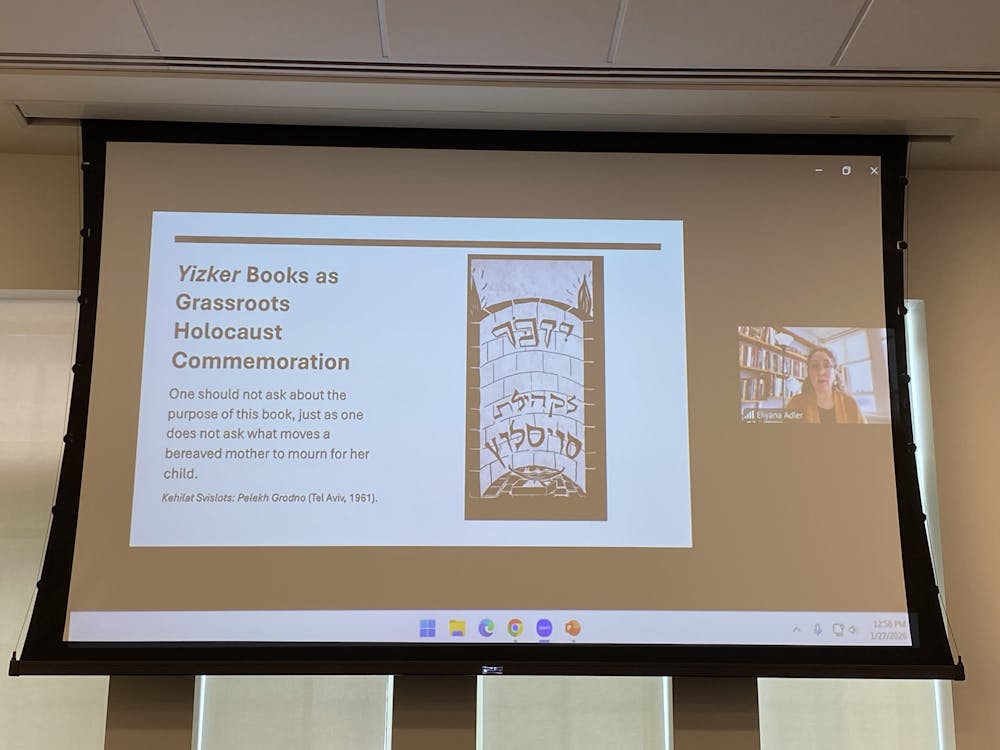

This year’s lecture, “Gravestones in Words and Pictures: Yizkor Books as Grassroots Holocaust Commemoration,” was presented by professor of history and Judaic studies at Binghamton University, Eliyana Adler. A press release from the University described Adler as: “a student and teacher of Eastern European Jewish history, with a particular focus on Poland and the USSR.” She is the author of two books and is currently writing a third post-Holocaust memorial book.

Dr. Clemens Sedmak, the director and professor of social ethics at the Nanovic Institute and integral to the lecture’s founding, opened the lecture. He later described the Holocaust as “a sad, terrible milestone in the history of Europe.” Having grown up in post-war Austria, he said it was important to set up this lecture so Americans could learn about the event and ensure it’s not forgotten.

“I think remembrance means we need to come together,” he said. “There is this beautiful idea that our memories are like plants, and you need to water the plant by talking about the memories.”

Due to the weather, Adler was unable to be on campus, so she, as well as several others watching, attended the lecture via Zoom. After being introduced by Sedmak, Adler began with a discussion of what happened to those who survived the Holocaust and how they commemorated the losses that they suffered during the war.

One way Holocaust survivors documented their home communities was through Yizkor books. Each is dedicated to a specific area or city, and is designed to discuss years of Jewish life and commemorate those who were killed. Book committees gathered to put them together, and Adler described their content as “communal, collaborative, comprehensive and commemorative.”

“They created maps, memory maps, not to scale technical maps, but maps about what they saw and what they felt,” Adler said. “Sometimes people had historical documents, occasionally. Sometimes people made artwork of their own, representing the town.”

Drawing on the images in Yizkor books, Adler noted that each conveyed distinct artistic messages that contributed to its deeper meaning. It was common, for example, to use symbols of light and darkness to convey messages of hope.

“It's only the book, the communal and collective endeavors of commemoration that live on,” Adler said. “Paper is stronger than stone and wood, and this new type of book is crucial to survival and to the future.”

Throughout the introductions to these books, there is substantial mention of these texts being used as a “matseyve,” the Hebrew term for a headstone or tombstone. Adler read one of these introductions, meant to be a physical reminder of how it feels to stand near the graves of loved ones and a monument to those who were lost.

“Soon after the war, in 1945, I was consumed by the idea of producing a book to personify a memorial to the Jews of our ravaged hometown, whom the Nazis destroyed,” Adler read. “A real monument to the unnamed dead and windblown ashes, an eternal light for their pure souls.”