Before “twee” was used as a genre label for bands like She & Him or ear, it was an insult, and it’s an insult my mom still uses. To the best of my knowledge, it means something like “too earnest” or “too affected,” so much so that it’s embarrassing. Zoomers utilize “cringe” for similar purposes, but there’s something “twee” captures that “cringe” can’t. I bring it up because I was afraid “Every Brilliant Thing” would be twee.

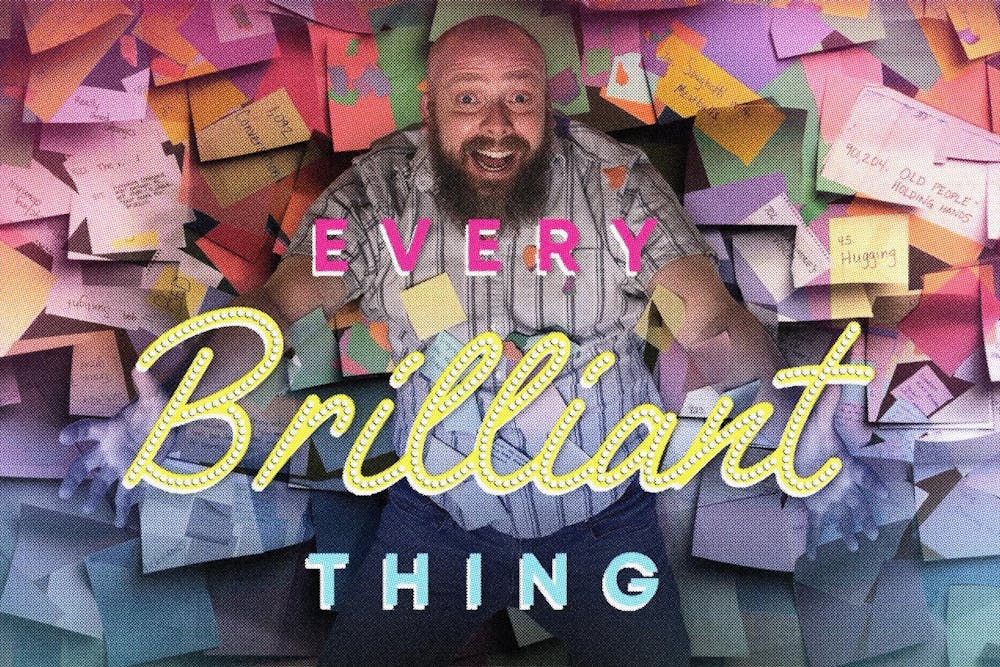

“Every Brilliant Thing” is a one-man show about a family affected by the mental illness and suicide attempts of its matriarch, told by the son who is coping by trying to list “every brilliant thing,” and it was performed at the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center (DPAC) this past weekend as part of this school year’s Presenting Series. Co-written by Duncan Macmillan and Jonny Donahoe, it debuted at Britain’s Ludlow Fringe Festival, and Brits — in my experience — tend to be pretty twee. Isn’t there something glib even just about the word “brilliant”? No American would try to name “every brilliant thing.” They’d probably go for the less pretentious option of “every beautiful thing.”

Everyone I knew who saw the show loved it though, and the advertising algorithm on Instagram was convinced I needed to see it too. So, to DPAC then I came. As I walked into the theater, the first usher I saw — a friend of mine — warned me the show came with an extra large helping of audience participation. I shuddered and thought, “There’s nothing more twee than audience participation.” The second usher — a stranger — only said, “Have a seat,” and then he laughed a wanton laugh that told me I was in over my head.

I deliberately sat far back from the front row and far away from the aisles, the seat least vulnerable to audience participation. Those nearby were clearly sitting in the area for the very same reason. While making small talk with the woman to my right, who had driven 80 minutes from the Fort Wayne area to see the show, she told me her friend was seeing it for the fourth time. I thought that was nuts.

After seeing “Every Brilliant Thing,” I still think that’s nuts — seeing any production four times in a row is nuts — but now I understand the impulse. The show was a little affected, yes, but it was also deeply affecting.

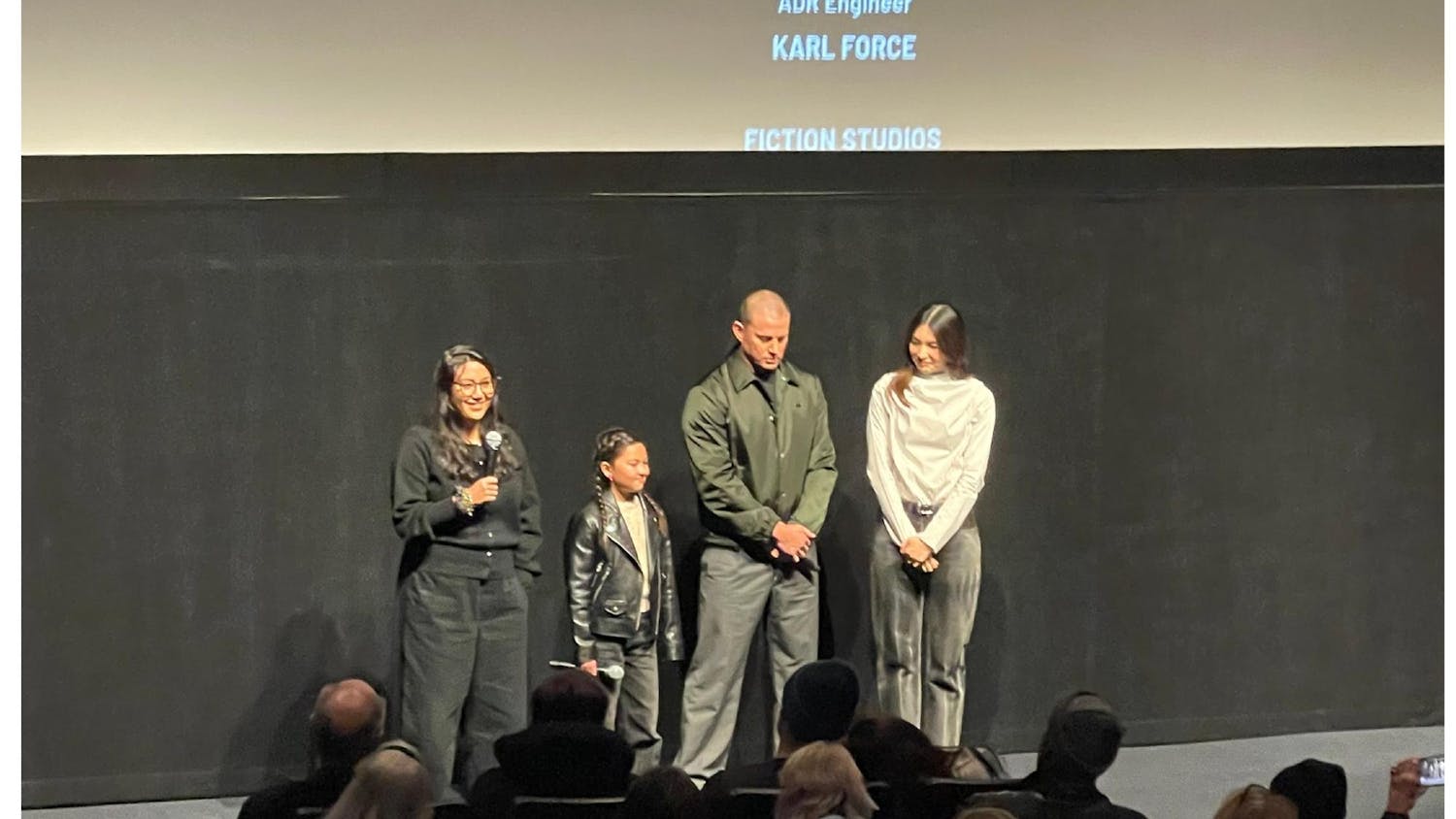

Just as an audience member’s suspension of disbelief clicks into gear at a certain point in the beginning of a theatrical performance, “suspension of cringe” clicked in like clockwork despite the script’s touchy themes and the production’s earnest treatment of those themes. Actor Matt Hawkins and director Stacy Stoltz successfully convinced the audience to follow the hero’s journey wholeheartedly, to put all their chips on the protagonist. They even got the stoic middle-aged husbands, dragged there by their wives, and the cagey, nervous and kvetching teenagers like me invested in the narrative.

Hawkins is a professor in the Department of Film, Television, and Theatre, which I think contributed immensely to the production’s success. A feature of this one-man show is that it occasionally isn’t one, with the performer press ganging audience members into being his scene partners. A man with a British accent in the front row played Hawkins’ father; a woman to his right played Mrs. Patterson, Hawkins’ school counselor; another played a veterinarian who euthanizes his dog; another played his wife. Perhaps because of Hawkins’ classroom experience — word on the street is that he’s an exacting and effective professor — he proved able to draw shockingly good performances from these untrained strangers. He led the father through an emotionally charged conversation, got some great improv out of Mrs. Patterson and coaxed a good-humored performance out of the veterinarian. At the advent of any coincidental occurrence, he was at the ready to squeeze the maximum effect from it.

“Every Brilliant Thing” felt a little bit like a modern, atheistic “Everyman.” It tackles the fear of death and explores the goodness of life. Its protagonist is unnamed. On the other hand, there’s a lot more to write home about in the plot department when it comes to “Every Brilliant Thing.” Nevertheless, just as “Everyman” presumably had a cathartic effect upon its medieval viewers, “Every Brilliant Thing” seemingly had the same upon its contemporary audience when I saw it on Sunday.

(The only thing I didn’t like about the show — a mistake by the playwrights and not by Hawkins and Stoltz — is that the script dissed Goethe out of nowhere. Why must he still catch strays from moralists in anno Domini 2025?)