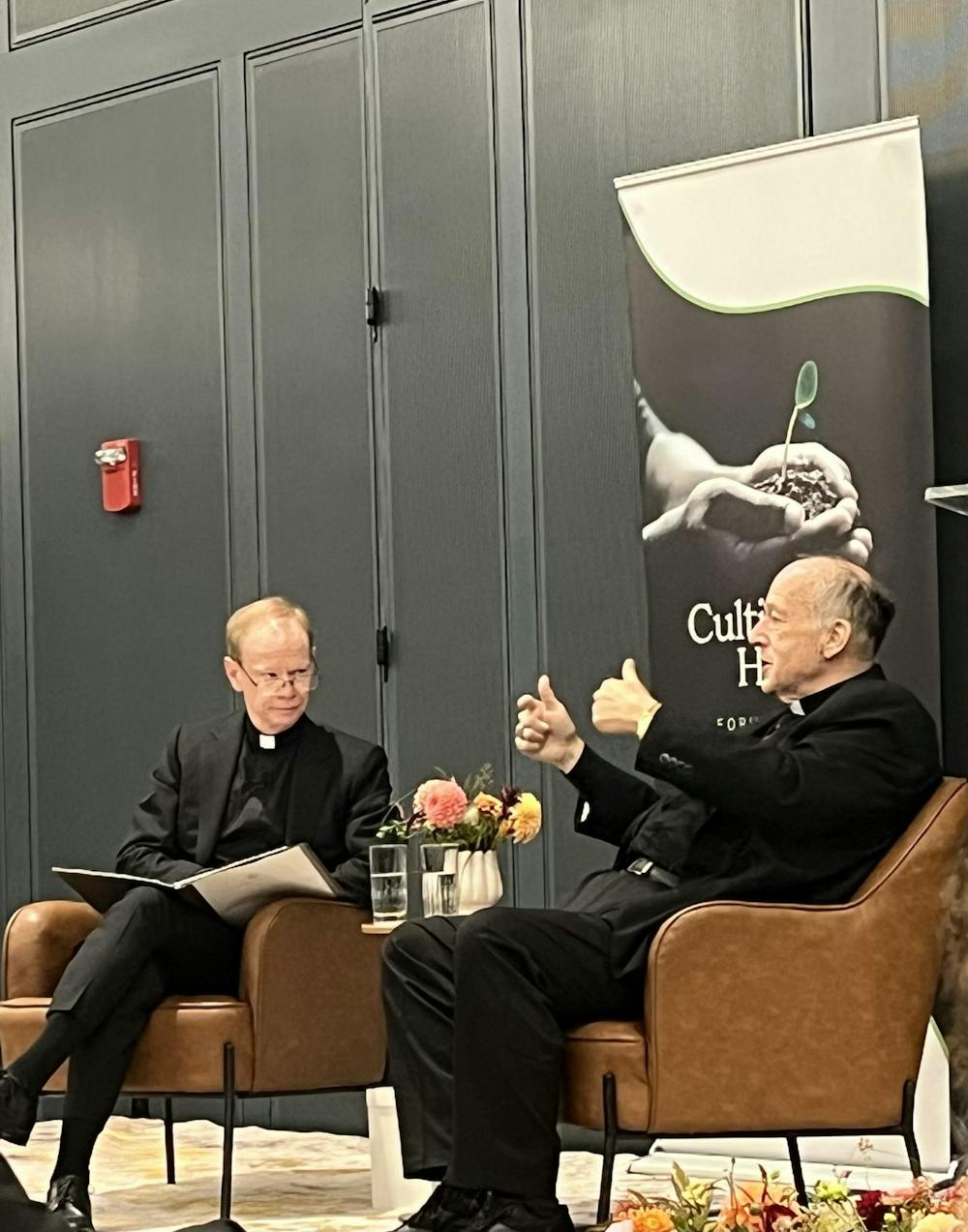

On Oct. 17, Cardinal Robert McElroy visited Notre Dame for a conversation with University President Fr. Robert Dowd titled “Healing our National Dialogue and Political Life.”

Now the archbishop of Washington, D.C., McElroy received a bachelor’s degree in American History from Harvard and both a master’s degree in American history and a doctorate in political science from Stanford University along with a doctorate in moral theology from the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. Pope Francis appointed McElroy to the College of Cardinals in May 2022 and to be the eighth archbishop of Washington on Jan. 6, 2025.

Dowd introduced McElroy as “an ideal person to have on our campus to talk about what it means to cultivate hope.” Cultivating hope is the theme of this year’s Notre Dame Forum, inspired by Pope Francis’ Jubilee Year of Hope.

McElroy began by describing his job in the archdiocese of Washington and comparing it to his work in the diocese of San Diego, where he served for 10 years.

“There are two other dimensions in Washington that I did not have in San Diego. The first one is that because it is the capital, many Catholic institutions in the country have either their headquarters there, educational institutions, social service centers. So part of my work as archbishop is collaborating with all of those groups in the city of Washington,” McElroy said.

McElroy has also been called to speak on public policy as the archbishop of Washington. “As the archbishop of Washington, as any bishop does, we have to speak to the moral dimensions of public policy from time to time. And because it’s in Washington, it has a resonance that it would not have elsewhere,” he said.

Although he speaks on the moral side of public policy issues, McElroy doesn’t believe his role is an inherently political one. “My primary role is to be a bishop of the communities in Washington. I’m not there primarily to speak on ... political issues. That’s not the centerpiece of what I do. And sometimes people expect that to be the centerpiece of what I do. The church has no specific role in the order of politics or the order of public policy. There is no specifically political role for the church, period,” he said.

McElroy also discussed the importance of transforming political discourse in America. Specifically, he emphasized the need to make three transitions, beginning with a shift from grievance to gratitude. “I think tremendously we have become a nation of grievance, where we focus more on what is lacking, and particularly what is lacking for me or my group, rather than on that which binds us together. So that’s our way out of this is in part going to be trying to recapture that which binds us together on this very deep level,” McElroy said.

The second transition is from the politics of warfare to shared purpose. McElroy described the politics of warfare as a shift in the United States since the 1990s, which he attributes to Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America” and the Clinton administration’s “War Room.” He also attributed this shift to social media and the increasing salience of party labels and identification, which McElroy believes have “become shorthands for worldview in the views of many people, perhaps a majority.”

McElroy said that Catholic teaching does not fit neatly with the political platforms of either major party in the U.S. “Catholic social teaching crosses the spectrum, is really bifurcated by our political structure in the present day. On the Republican side, there tend to be more issues like abortion, euthanasia and certain aspects of religious liberty. On the Democratic side, there’s more coalescence with issues, say, of poverty, of peace and of the environment and human dignity,” McElroy said.

In light of this, McElroy believes the third transition needs to be from insularity to compassion.

“In one way it’s good for the church because it prevents us from ever siding with any party, because our views are absolutely bifurcated. But it makes it hard for Catholic voters. There are very few political officials who really represent even 70% of Catholic social teaching because of that barrier right in the middle that cuts it in two. So I think compassion is a way to do it. We’re in a tough time on these questions, but it’s not an irredeemable time,” he said.

McElroy also spoke about what the U.S. political system can learn from the church and vice versa. He referenced Pope Francis’s encyclical “Fratelli Tutti,” which “talks about what love of neighbor is supposed to mean for us.” He thinks the encyclical’s ideas “would be a great help in our society for us to really grapple with that as individuals and as communities and as citizens and believers too in our public roles. I think it’s a vision that the love of neighbor is all-encompassing.”

Additionally, McElroy believes the political system can benefit from the church’s “synodal type of approach to discussion.”

“We have to get back to discussions across lines, in which we can talk about public policy issues and divisive issues without going to our corners. I think the church’s synodal way of doing it engages in hard questions where people disagree,” he said.

McElroy called on attendees to be pilgrims of hope and practice bipartisan discussion. Primarily, he thinks being a pilgrim of hope means “working on the level of dialogue within the University.”

McElroy said he is ultimately hopeful about the future of political dialogue, especially based on what he has seen in parish communities. “I still find that the greatest source of hope in the church and the world,” McElroy said.