On Tuesday afternoon, Kellogg Institute Fellow and economics professor Enrique Seira Bejarano gave a lecture at the Hesburgh Center for International Studies as part of the Kellogg Institute seminar program. During the one-hour lecture, Bejarano discussed the link between government corruption and trust in democratic values.

Bejarano, who earned his Ph.D. in economics from Stanford University, began his lecture by defining apex corruption as “the use of public office for private gain by high-ranking politicians, bureaucrats and judges.”

He emphasized the consequences of this type of corruption, saying that citizens may stop trusting the institution which apex politicians have control over or perceive these politicians as models or examples.

The remainder of the lecture focused on the central question: “Is apex corruption causally undermining democracy?’’

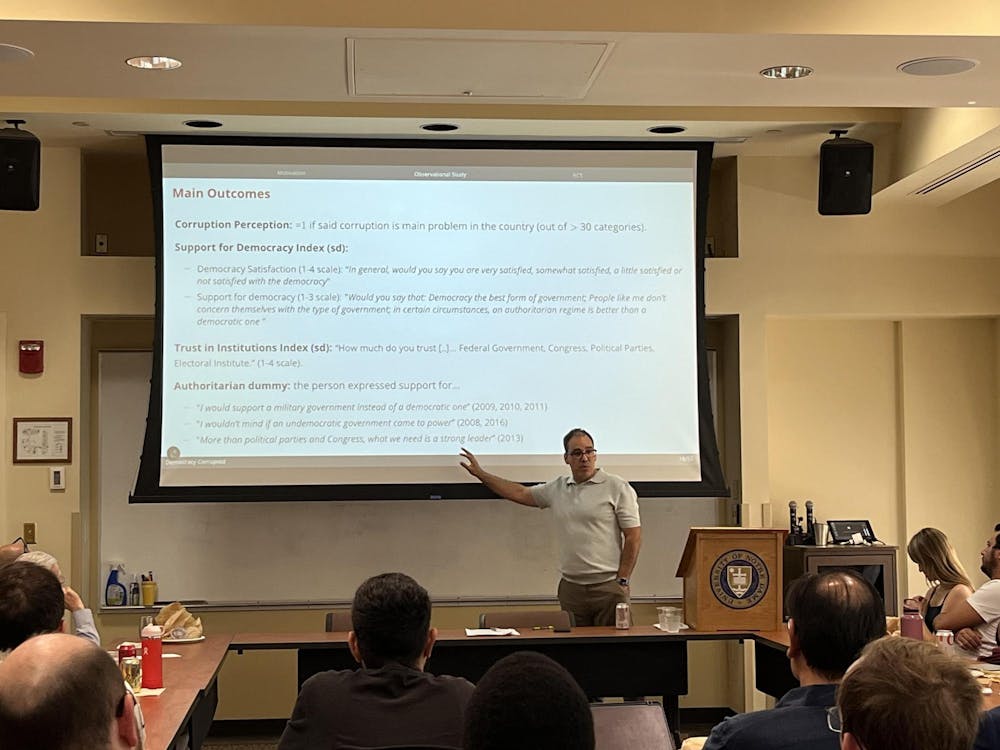

Bejarano used two methods to answer this question. First, he conducted an observational study using data about corruption scandals by high profile politicians from 17 Latin American countries over 10 years. Afterwards, Bejarano and his colleagues ran a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Mexico to determine whether apex corruption impacted democratic values and associated behaviors.

For the observational study, Bejarano used social media and news archives to build his data set.

“First, we want to know when a corruption scandal happened, the exact dates and where. And we want to know the apex politician was involved. So what we did here was scrape the Twitter accounts for each of the 17 countries for the four main news channels of each of these countries for 10 years, looking for words, critical drive, corruption, etc,” he said. “It was a bit painful, but we ended up with a data set of corruption scandals for very high-level politicians.”

To draw his conclusion, Bejarano compared the data about the timing of corrupt acts with data from the Latinobarometer public opinion survey, which asks participants questions about their perception of corruption and satisfaction with democracy.

Bejarano concluded that after people hear about a corruption scandal, they are more willing to have an authoritarian in power.

“This may be driven by pessimism. People may be pissed off right after seeing the president’s testimony, but it doesn't show on other opinions, so they're not angry across the board. [Their anger] seems to be focused on the political system,” Bejarano said.

Next, Bejarano described the random field experiment he conducted in Mexico. “We expose[d] citizens, just before an election ... to footage of politicians taking statutory action from the incumbent party, from the opposition party,” he said. “Then we can manipulate the content. We can manipulate the timing, randomly, how close to election we expose them to that. And then we can measure, we link this with an incident data of voting. This is not self-reporting data, this is actual voting measured by email.”

The field experiment allowed Bejarano to study the effect of apex corruption on democratic values over time. “What we do in the RCT is we go to homes and revisit them months later. It's a better setup to look at persistence. The farther I go here, the less credible the data strategy is. It's more different people, different neighborhoods. But I, we try to do something on persistence of the RCTs,” he said.

To recreate the experiment for the audience, Bejarano showed the footage of the brother of the president of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, taking bribes and counting stacks of cash, as well as videos of senators from the opposition parties taking millions in bribes. “I'm going to show you actual footage of politicians taking statutory action ... this is not uncommon in Latin America,” he said.

Bejarano concluded the lecture by emphasizing the consequences of corrupt leadership. “Apex corruption revelations do decrease stated support for democracy and democracy-supporting behaviors like voting and willingness to be electoral observers,” he said.

The effects of apex corruption extend beyond democratic values. “They also decrease trust, not only in democratic institutions but in neighbors too, as well as increasing stealing, suggesting beliefs of trustworthiness and internalized norms change,” Bejarano said.