One of my proudest moments during my summer fellowship was learning how to draw a cow.

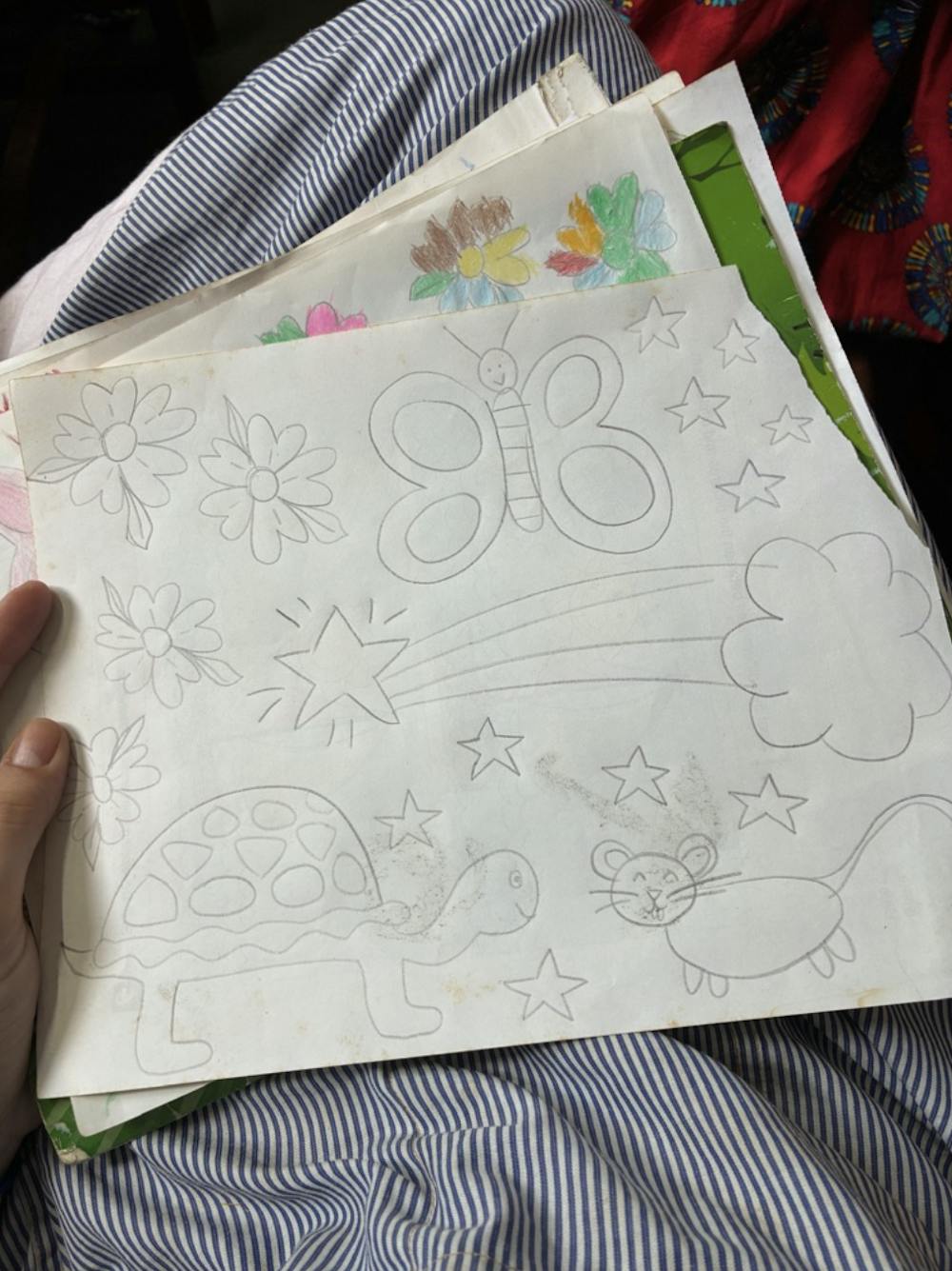

In fact, I have the art of drawing cows (and other cartoon-like animals) down to a science. I spent hours upon hours at my volunteer position at the Nirmal Hriday Home for the Dying and Destitute in Kolkata, India, doodling and sharpening colored pencils. I was like a machine — by the end of my fellowship, I could knock out a whole coloring page’s worth of doodles in less than two minutes. Turtles, mice, butterflies, even peacocks, all smiling in graphite and white, ready to be passed to one of the patients to color in.

The women in the female ward where I worked praised me for my doodles, often asking for a coloring page as soon as I walked in the door. Despite our respective language barriers, it was clear to me that I had found my calling in the Home: resident (amateur) cartoonist.

This position may seem incredibly unimportant compared to the other work done in a resource-limited medical setting. One could argue that my time would be better spent rolling bandages, sorting through boxes of expired medication or even observing wound care. I did all of these things and more during my summer, but nothing felt as important or impactful to me as my dedicated coloring book hour before lunch.

We spent most of the morning transferring the female patients from their beds to a recreational area consisting of several long picnic-style tables and benches. Most of the women were immobile, and with so few nuns and workers, this process took the better part of an hour. After feeding the women breakfast and another hour or so transporting them to the bathroom and back, it was finally time for some entertainment.

The back corner of the recreational area held a looming wooden chest full of discarded materials from previous, well-meaning volunteers. Nail polishes that had long since dried up, baby dolls missing limbs with lazy eyes and puzzles so worn that no one could even hope to piece them together anymore. It was a sad collection of mostly donated items meant to cheer the female patients up, but instead, the ‘entertainment’ prompted most of the women to slip into their mid-morning nap while still at the table.

One morning, while digging through the chest with my co-fellow, Zoie, we discovered a stack of old books, newspapers, a single coloring sheet and a meager box of colored pencils. By this point in the morning, we had already exhausted the crusted nail polish and disfigured slinkies, and we were desperate for a new source of boredom relief.

As I brought the art supplies over to a table of the more lively patients, they all started smiling almost immediately. As I set down the sole coloring page between two women, they each grabbed a colored pencil and worked on their respective corners, while the rest of the women at the table reached for the slightly damp and wrinkled newspaper to doodle and write on. It was glaringly apparent that the art supplies were the most exciting thing to come out of that decrepit wooden chest in months.

Soon enough, the single coloring sheet was covered in a rainbow of scribbles, and the female patients looked at me, gesturing for another one. After flipping through all the old books and newspapers with no luck, I decided to doodle a few hearts and stars for the women to color in. Within a few minutes, the rest of the table was requesting their own pages. I was completely delighted that I could be of some real service to them — after weeks of attempting manicures with the dried-out nail polish, I was finally providing a genuine source of entertainment.

On our way into work the next morning, Zoie and I stopped by a small stationery shop across from the bus stop. I bought a large pack of plain white paper and a pack of 30 colored pencils for a whopping 200 rupees (or roughly $2.50) and began constructing my black and white doodles on the bus ride to work.

This became a ritual for the rest of my summer. Soon, I picked up on the women’s favorite animals to color. Sanda loved elephants, Mishka favored peacocks and Sumi preferred to write short stories about herself in her flawless English to slip into my apron pocket before I took my chai break. I even began writing their names in big bubble letters at the top of each page to personalize them more, which proved to be an immense source of joy. I will never forget the way Mishka’s face filled with delight the first time she saw her name designated on her personal coloring sheet. Watching the women recognize their own names on each page made me feel as though I was finally helping to restore a piece of who they were.

Our coloring breaks were the clear highlight of not only the patients’ days, but also mine. I loved to slow down and sit with them in the mornings, often accompanied by the dull monsoon winds outside the windows or their soft chattering in Bengali. It was in those moments that I felt most connected to my work; although bearing witness to patients’ medical care was impactful to me in ways I can’t begin to describe, I feel undeniably drawn to quantify my summer not in the number of procedures I witnessed, but rather in the number of coloring sheets I made.

This week, while slightly bored in class, I found myself doodling a small cow in the corner of my notebook. I didn’t realize what I was doing until it was nearly finished — as I mentioned, it’s down to a science now — and started to smile to myself as I reminisced about the vibrant cartoons and our morning coloring book hour.

Ivy Clark is a senior pre-med studying neuroscience and behavior with a minor in global health and the Glynn Program. Despite living in the midwest her entire life, she has visited 11 countries and is excited to share her most recent endeavors working with the Missionaries of Charity in Kolkata, India. If Ivy could get dinner with any historical figure, it would be Paul Farmer or Samantha Power, whose memoir inspired her column name. You can reach her at iclark@nd.edu.