The last time I saw Ernest Morrell was in the offices of the Dean of the College of Arts and Letters in O’Shaughnessy Hall.

It was late September, and I was readying a fellowship application for the National Academy of Education. Truth be told, it was a long-shot. I am an English Ph.D. student who studies depictions of formal schooling and assimilation in modern Latino novels and memoirs. My dissertation, tentatively titled “Assimilation through Education: Individualism, Solidarity and the American Dream in Contemporary Mexican American Literature,” examines the intertwining of academic achievement and socioeconomic mobility in the storytelling of second-generation Americans.

From what I could see, this fellowship was aimed at people in more traditional educational fields, such as sociology. Still, Morrell encouraged me and showed enthusiasm for my ideas. All the while, he prompted me to think about how I could convey my message to a broader academic audience outside my discipline. Of all the professors on my dissertation committee, he was the one grounded in education, which made him a vital reference as I worked to articulate my ideas at the intersection of several fields.

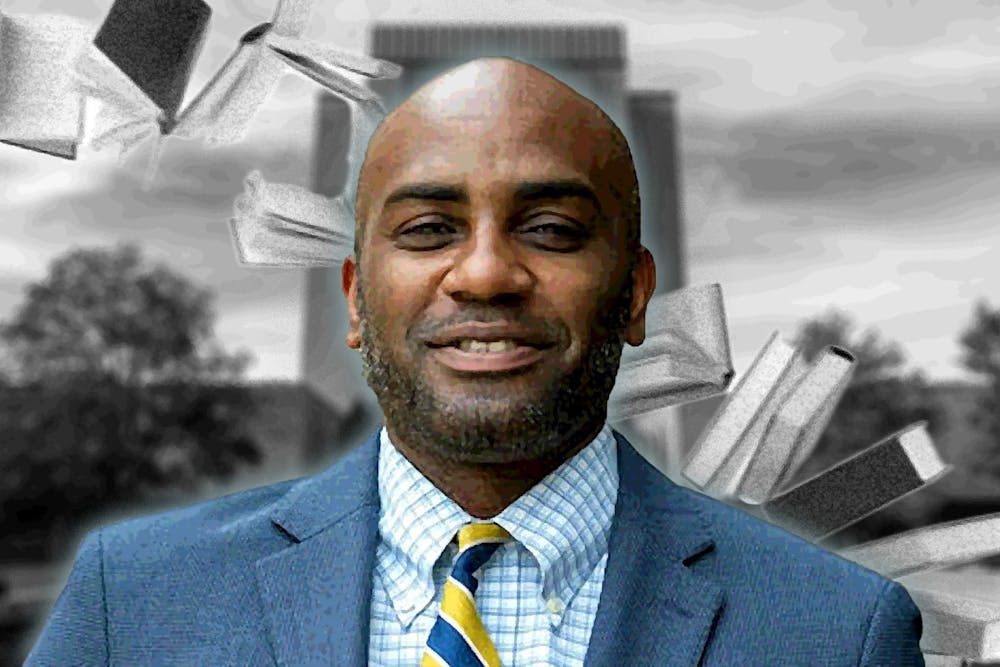

In early February, Morrell passed away after a years-long battle with cancer. He was 54 years old. He was affiliated with the English Department and Africana Studies as a professor and served as the associate dean for Humanities and Faculty Development in the College of Arts and Letters. Morrell is survived by his wife Jodene Morrell, a teaching professor and associate director of the Notre Dame Center for Literacy Education, and by his three children, Skip, Antonio and Tripp.

Morrell was one of the most accomplished scholars I have ever met. His resume was inspiring and intimidating. He authored more than 100 articles, book chapters and research briefs, and wrote or edited 17 scholarly books. His work has been cited more than 11,000 times and garnered him multiple accolades, such as induction into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, one of the most storied learned societies in the country. Key to his success was his collaborative approach to authorship and his willingness to work with up-and-coming scholars. Over the course of his career, he served on over 100 dissertation committees as a director and as a reader.

What I liked most about Morrell was that he always emphasized the importance of community-oriented research. Having been a high school teacher for five years in Oakland, California, Morrell understood the transformative potential of novels, memoirs and poetry in the high school classroom, especially in working-class communities. According to Joyelle McSweeney, chair of the English Department, it was precisely this quality that made him such a valuable member of the Notre Dame community.

“With his scholarship on literacy and pedagogy, he was a real bridge between the way we imagine the texts and the communities to which they are most valuable,” McSweeney said. “He looked at how the written word moves in the world and how literacy functions to empower people.”

My dissertation advisor, Mark Sanders, chair of Africana Studies and a professor of English, started at Notre Dame at the same time as Morrell, in the fall of 2017. The two were close associates and frequently brainstormed ideas to make Notre Dame a more inclusive place, especially after they both moved into administrative roles based in O’Shaughnessy Hall.

“Ernest was one of the most vested and compassionate administrators I’ve ever worked with,” Sanders said. “He understood how to get things done. He was a world-class scholar, the highest caliber of academician the American academy can produce.”

Morrell was a voracious reader. He and I shared a passion for Luis J. Rodriguez’s memoir, “Always Running: La Vida Loca: Gang Days in L.A.” In part motivated by Morrell’s enthusiasm, I decided to dedicate a chapter of my dissertation to analyzing the memoir’s complex depiction of assimilation, masculinity and schooling. Beyond the storytelling, we appreciated the reception the book enjoyed among young people in the 1990s and early 2000s, especially Latino high school students facing school violence and discriminatory tracking systems.

Of course, one of Morrell’s greatest intellectual inspirations was the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. Freire’s most famous work is his “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” which advocated for an approach to formal education that draws on student backgrounds rather than a one-size-fits-all banking model of instruction. Freire pushed for increased educational opportunities for poor students, people in rural communities and for adults. Morrell’s enthusiasm for Freire inspired him to co-author a book with his wife, Jodene, entitled “Paulo Freire for Children.” The collection recounts their experiences as classroom teachers and educational researchers through a Freirean lens.

One of Morrell’s greatest scholarly contributions was the idea of “critical literacy.” By critical literacy, Morrell referred to the need to cultivate awareness of the overlapping political, social and ideological contexts in which language operates. Teachers, Morrell argued in his 2008 book, “Critical Literacy and Urban Youth: Pedagogies of Access, Dissent, and Liberation,” must arm students with the ability to “speak back” to power. This sort of “youth-initiated pedagogy,” he writes, fosters “engaged citizenship and personal emancipation.” Though I lean more towards literature than literacy, I have used his terminology as a guiding compass to read novels and memoirs for use in my study.

Over the years, I would run into Morrell randomly in and around campus. Usually, he’d be dressed in business casual: a dark suit over a light-colored dress shirt, no tie. He favored a tan, low-brimmed hat and black square-rimmed reading glasses. His sartorial choices gave him an air of sophistication and openness. Even though it had been decades since he had taught high school, he still carried that teacher vibe, in a good way. It was the kind of energy that made you feel at ease, whether you were chatting with him in the middle of the street or sinking into the plush sofa couch he kept in his office for visitors. He was a good dude. Ernest, you will be missed.

Oliver "Oli" Ortega is a Ph.D. candidate in English specializing in contemporary Mexican-American and Latino literatures. Originally from Queens, NY, he has called the Midwest home for 15 years. He lives in downtown South Bend. You can contact Oliver at oortega1@nd.edu.