“Diciannove” forces you to become intimately acquainted with the main character, Leonardo, a 19-year-old student who leaves his hometown of Palermo to study business in London. Before he even starts his classes, Leonardo decides to make an impulsive switch, enrolling at the University of Siena to study literature, where he finds the lectures boring. After receiving what is the American equivalent of a B- on an oral exam, he elects not to go to classes and begins a sort of self-study of Italian literature where his antisocial tendencies begin to be exacerbated.

One of the greatest merits of the film is its ability to simultaneously incorporate realism with autobiography — two terms that ought to go hand in hand but rarely do. Autobiography or autofiction, to me, is a genre of film and literature that is susceptible to multitudes of issues, including but not limited to: unproductive navel gazing, dishonesty and the laziness that (generally) comes with picking such a genre. Giovanni Tortorici, the director of “Diciannove,” manages to avoid these pitfalls as he courageously portrays himself as he was — a repulsive, tepid, antisocial, ungrateful, egomaniacal 19-year-old; furthermore, he forces you to spend the entire film intimately acquainted with him in his less flattering states. Tortorici’s primary concern seems to be the accuracy of his depiction, and the artfulness of the film flowed out of that goal rather than any manufactured telos.

To help increase the reader’s understanding of why I appreciate Tortorici’s execution of the autobiographical genre, I want to contrast this film with “Buffalo ‘66,” another semi-autobiographical film, directed by the infamous Vincent Gallo. This film, while highly acclaimed, takes the opposite direction. The humiliations of the main character, Gallo himself, are either artificially replaced with the poor upbringing of one-dimensional parents or are “humiliations” so socially accepted and “heartwarming/twistedly admirable” that they manipulate the audience into thinking Gallo is showing a sort of vulnerability, while he never actually deigns to drop the charismatic mask. Tortorici’s film doesn’t do this. His character’s mistakes are not softened or manipulated. Leonardo is banally, unattractively “evil” — evil’s most real manifestation. Even the potential “goodness” that this character has is not immediately accessible by watching, if accessible at all. At the end of the film, the supposed resurrection of his character, “the arriving-at-the-age,” amounts to blind faith.

The viewer of the film never gets that close to Leonardo’s thoughts. While emotional turmoil is expressed, and we get hints of internal monologue through various rants, Leonardo, as a thinker, is still mostly unknown. This partly has to do with the medium. Unlike “Catcher in the Rye” or “A Search in Lost Time,” where burgeoning artist first-person narrators have their penetrating insights illustrated, sensitivity cataloged and interior depth shown, “Diciannove” is limited to portraying Leonardo’s external, visual world. Still, despite the limits of the medium, Tortorici portrays interiority novelly. Moods are portrayed vividly through the beautiful music, vibrant tones of color and cinematography, and accompanying thoughts are gracefully implied indirectly through action, but often left ambiguous.

Throughout, the viewer is invited to speculate about the reason behind unclarified actions — invited to psychoanalyze, before Tortorici partially does it for us. The grand finale of Leonardo’s humiliations is at the hands of a man who can be inferred to be a psychoanalyst. The analysis is flippant but sharp and penetrating, and the final scene of the film implies it had some effect.

Addressing the apparent paradox at the beginning of the article could be approached in two ways. I could either take the weaker route in solving the paradox by proclaiming the beauty and ugliness are separated temporally in the film, i.e., are beautiful sections and ugly sections. Yet that answer is clearly unsatisfying.

I hold rather that the depravity and uncompromising reality of the depiction of Leonardo is combined with narrative magic and artistic touch of the director to form a “transcendental” union that straddles the supposed contradiction.

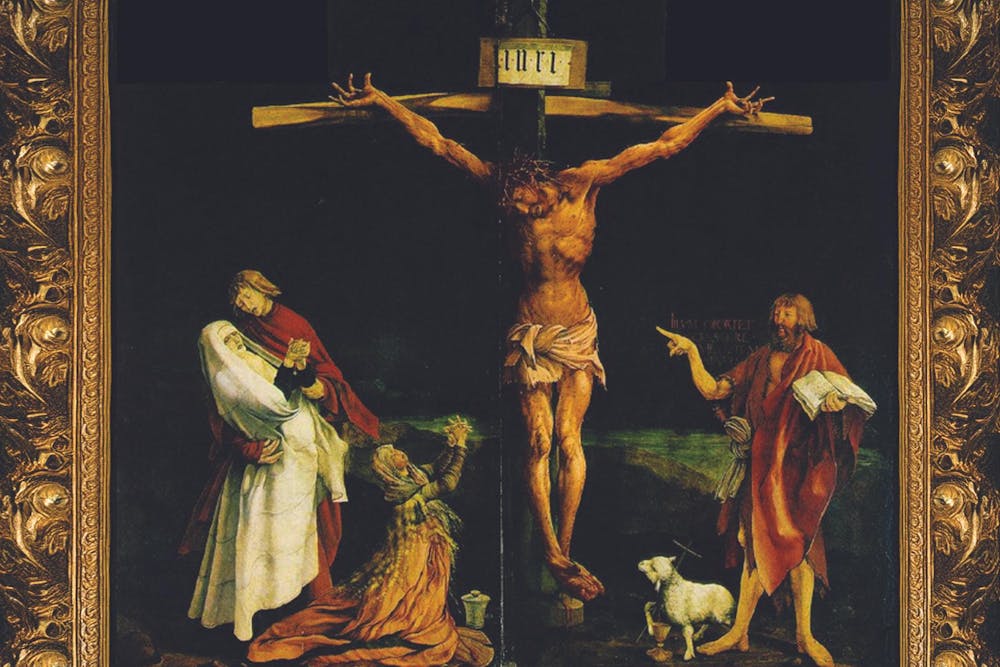

A poetic explanation of this straddling will in this case be deferred to author Joris-Karl Huysmans’ articulation of the appeal of an analogous work of art, Matthias Grünewald’s painting of Christ’s crucifixion:

“Never before had naturalism transfigured itself by such a conception and execution. Never before had a painter so charnally envisaged divinity nor so brutally dipped his brush into the wounds and running sores and bleeding nail holes of the Saviour. Grünewald had passed all measure. He was the most uncompromising of realists, but his morgue Redeemer, his sewer Deity, let the observer know that realism could be truly transcendent. A divine light played about that ulcerated head, a superhuman expression illuminated the fermenting skin of the epileptic features. This crucified corpse was a very God, and, without aureole, without nimbus, with none of the stock accoutrements except the blood-sprinkled crown of thorns, Jesus appeared in His celestial super-essence, between the stunned, grief-torn Virgin and a Saint John whose calcined eyes were beyond the shedding of tears.”

To conclude: I hold this film in high esteem, yet others have not and, I predict, will continue to not pay it the respect it deserves. There are two reasons for this: The first is that it’s in Italian and few people enjoy reading subtitles, especially when the format of this movie makes it so that subtitles are especially difficult to execute with poise; The second is because Leonardo’s repulsivity will necessarily turn people off from enjoying it.

Still, its content and depictions are relevant and the director’s artistic semi-experimental touch is interesting and unique. You should watch this film.