Last semester, I heard a fellow student complaining about law school, and in particular, people who get extended time on the bar exam, and who said something along the lines of “some people aren’t meant to be lawyers.” I, as someone with aspirations of being a lawyer and who has extended time on tests, was offended. I wanted to say something in defense of myself and of the many people like me whom I’ve met over time with conditions similar to mine, but, afraid to be seen as one of those people “not meant” for certain careers, I didn’t say anything.

I write this article in part in conversation with an excellent opinion by Hannah Alice Simon, which discusses, in part, the marginalization of disabled voices, especially when it comes to AI. While Simon focuses on the invisibility of disability, I instead want to focus on the defining struggle of my experience of disability, unwanted visibility. Throughout my childhood, getting the accommodations I needed to succeed meant being exposed as different. In elementary school, every day at around noon, all the kids with a disability in a class were taken out at the same time for an hour. In middle school, I had to take a small study hall instead of a language and missed out on three years of foreign-language education. No one knew exactly what was wrong with me, and even if I explained it, the average preteen and most adults didn’t actually seem to care. I was just an aberration, someone with an unknown deficiency. I must pause, though, and say that none of my fellow disabled classmates were just different. The kids I sat in the study hall with were creative authors, brilliant engineers and all-around wonderful people in the making. After a while, though, things got easier. I found medication that works really well with my disability, and I gradually needed accommodations less and less. I got to blend back in. I got to stand out for my interests and achievements instead of the disability I had no control over.

However, in college, I’ve found the promise of blending in to be a foolhardy endeavor. Even with the manifestation of my particular disability, my disability still bleeds into my everyday life. I’m dependent on medication, which can be jeopardized by shortages or idiosyncratic regulations in different jurisdictions. I still have visible symptoms in my day-to-day that I’ve had friends remark on more than once. I may be able to blend in better than those with other conditions, but I’m still different and will be different for the rest of my life.

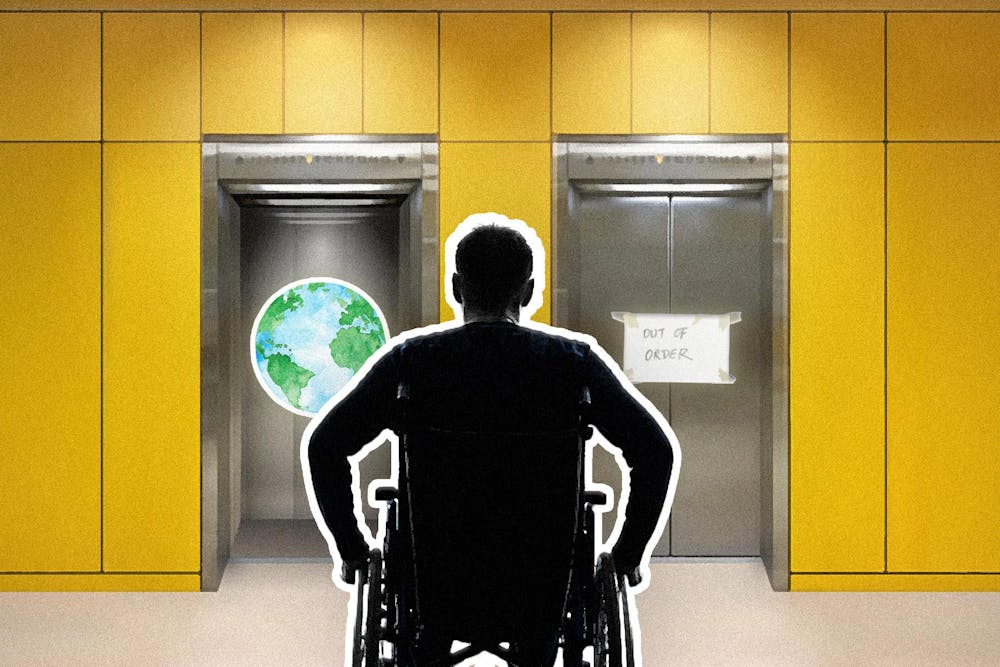

So if fading into the background is impossible, how do we advocate for a caring society that will not coldly regard us as different?

I think the solution lies in pointing out the false dichotomy of difference. I have spent this article obsessing over the two camps of disability and “normal ability,” and my attempts to blend into “normal ability.” However, “normal ability” is not so much a concrete category as a fuzzy ideal that most people will eventually fall short of. Most people reading this will become disabled in old age. Before old age, many of us will be temporarily or permanently disabled by illness, injury or some other unfortunate set of circumstances. There is nothing you can do to avoid such a possibility. Even if you refuse to get near a motor vehicle, never touch drugs or alcohol and spend every day inside 24/7, there’s still a million and one ways for you to become disabled. The struggles of the disabled community are not the problem of other people, but a very real issue for everyone reading. To paraphrase political philosopher and Notre Dame professor emeritus Alasdair MacIntyre, disability rights are not a special interest of a small community but the concern of the whole political society.

I conclude by not asking you to advocate for disabled voices or to think hard about how you treat disabled people, not for my sake or others, but for your own. Many of you will one day slip across the line from “normally abled” to disabled. In a world where four out of 10 disabled people will face discrimination at work, receiving healthcare or applying for benefits, that may sound scary. The good news, though, is that you have time to build the kind of world you’d want to be in if you were disabled.

Contact Patrick Kompare at pkompare@nd.edu.